![]()

Of the many songs mentioned in the Abbé Fleuriot’s manuscripts, two at least seem of textual significance: En Passant par la Lorraine and La Pernette.

En Passant par la Lorraine

You can hear the song here or download it here.

This is the song Jacques tells us was a favourite of the ‘old Seigneur’s’, which Hélène Gilbert used to sing to André when he was very small. We see her sing it to him again when he returns home hurt after the fight with Stefan, and André hums it himself as he prepares for the raid on the Spanish barracks.

The song itself is an unsurprising choice. It is a very old piece, supposed to have been first set to music in the 16th century by Orlando Passus, and although it’s mostly thought of now as a nursery rhyme for children, it was long associated with the French army and is indeed still a stirring and poignantly evocative military march. In an essay celebrating the 60th anniversary of de Gaulle’s Appel du Juin 1940, the Second World War veteran Pierre Lefranc recalls movingly an occasion in June 1943 when the Free French army marched through London to the military music of their own country, and notes in particular that: We marched to the strains of En passant par la Lorraine towards the statue of Marshal Foch with tears in our eyes.

The lyrics, however, suggest the song may have a greater significance than the mere military:

| En passant par la Lorraine, avec mes sabots, | Going through Lorraine, with my shoes |

| En passant par la Lorraine, avec mes sabots, | |

| Rencontrai trois capitaines, avec mes sabots, | I met three officers, with my shoes |

| Dondaine, oh ! Oh ! Oh ! | |

| Avec mes sabots. | |

| Rencontrai trois capitaines, avec mes sabots, | I met three officers, with my shoes |

| Rencontrai trois capitaines, avec mes sabots, | |

| Ils m'ont appelée vilaine, avec mes sabots, | They called me ugly, with my shoes |

| Dondaine, oh ! Oh ! Oh ! | |

| Avec mes sabots. |

Subsequent verses each change the key line, so that the whole story reads :

| Ils m'ont appelée vilaine. | They called me ugly. |

| Je ne suis pas si vilaine, | I’m not so ugly, |

| Puisque le fils du roi m'aime, | since the son of a King loves me. |

| Il m'a donné pour étrenne, | He gave me for a present |

| Un bouquet de marjolaine, | a bouquet of sweet marjoram |

| Je l'ai planté sur la plaine, | I’ve planted it in the field. |

| S'il fleurit, je serai reine, | If it flourishes, I shall be queen, |

| S'il y meurt, je perds ma peine! | But if it dies, then I’m wasting my time. |

(Translated Edward Morton)

‘Sabots’ can merely mean ‘shoes’ in French, but at this time the word was more commonly applied to rustic peasant shoes, often of wood, like clogs. The story is thus of a low-born girl, who despite the derision of others is beloved by a nobleman – a tale with obvious resonance in Honour and the Sword.

The original application of the song is lost, although one theory claims it is about Anne of Bretagne who became queen to two successive French kings. There is certainly a popular French folksong ‘C’ètait Anne de Bretagne, Duchesse en sabots’, which imagines her wearing rustic clogs for her first meeting with the king, and contains many specific verbal parallels with En passant par la Lorraine.

La Pernette

This is the song whistled so often by Pierre Gilbert, and the one Carlos Corvacho remembers particularly at the end of chapter 14.

‘La Pernette’ can mean either ‘the lost one’, or simply be a generic term for a young girl, following a specific hairstyle, ‘la perna’. The song existed as a chanson de toile as far back as the 12th century, appears in a Namur manuscript in 1467, then later in the famous Manuscrit de Bayeaux. It was not noted in its existing form until the 19th century, so the original tune is probably lost, but the words have carried on, and a version is still sung today in the popular ‘Ne pleure pas, Jeanette’.

There are several different versions of the lyrics, all concerning a girl who is questioned as to why she is weeping. The main question/answer exchange in all versions follows a pattern like this:

| Son père lui demande | Her father asks her |

| Pernette qu'avez-vous? | 'Pernette, what's up with you? |

| Avez vous mal de tête | 'Have you got a headache |

| Ou bien le mal d'amour? | 'Or are you just love sick?' |

| N'ai pas le mal de tête | 'I haven't got a headache, |

| Mais bien le mal d'amour | 'But my heart is breaking through love. |

| Ne pleure pas Pernette | 'Don't cry, Pernette, |

| Nous te marierons | 'We'll get you married |

| Avec le fils d'un prince | 'To the son of a prince |

| Ou celui d'un baron | 'Or perhaps of a baron.' |

| Je ne veux pas d'un prince | 'I want none of your prince |

| Ni du fils d'un baron | 'Nor the son of a baron. |

| Je veux mon ami Pierre | 'I want my lover Pierre, |

| Celui qu'est en prison | 'The one who's in prison.' |

| Tu n'auras pas ton Pierre | 'You can't have your Pierre, |

| Nous le pendouillerons | 'We're going to hang him.' |

| Si vous pendouillez Pierre | 'If you hang Pierre, |

| Pendouillez moi avec | 'Then hang me beside him.' |

(Translated Edward Morton)

This is, in fact, what happens – Pierre is hanged, and his faithful Pernette is hanged beside him. It may, perhaps, be reading too much into a simple chanson, but it seems at least possible that some of what happens later may have been inspired by the theme of this song.

General Songs

Although En passant par la Lorraine and La Pernette are of the greatest textural significance, there are several other pieces mentioned in the manuscripts. Most would have been over a hundred years old at the time, which is not perhaps surprising in a world before recordings, when it might take many years for a song or tune to travel to a remote country district such as the Saillie.

Bransle des Chevaux (‘The Horses’ Polka’) is a 16th century piece attributed to Thoinot Arbeau, and an obvious choice for Pierre Gilbert the horsemaster. In chapter 2 Jacques tells us ‘He whistled a lot, my Father, he was brilliant at it, he could do Bransle des Cheavaux with all the twiddly bits, and I loved that best.’ It’s certainly very cheerful, and for Jacques, it is the tune that comes to represent the rare moments of happiness of his childhood, when his father carried him on his shoulders and pretended to be a horse. You can listen to it here.

Il est bel et bon (‘He is both handsome and virtuous’) by Pierre Passereau is a 16th century Renaissance chanson in the style of a madrigal, which is still performed today. In chapter 9 Jacques tells us ‘there were a bunch of men singing ‘Il est bel et bon’ very badly’ in the village alehouse, the Quatre Corbeaux. Listening to the complexity of the piece, it is clear that sung by drunken peasantry this would have sounded very horrible indeed. You can listen to it here.

Triste España (‘Spain, Sad Spain!’) by Juan del Encina is a sentimental Spanish piece composed in 1497 on the death of the Crown Prince. It is perhaps ironic that this is the piece Anne hears at the banquet in chapter 16 when the tragic news is brought to Don Francisco. That she refers to the ‘sickly sound of the guitars’ says more about her mood than it does the beauty of the melody. You can listen to it here.

Guárdame las vacas (‘Tend the cows’, a 16th century piece by Louis de Narváez) is the tune to which Anne and Florian listen through the floor in chapter 18. It is a gentle, pastoral melody for the guitar, appropriate perhaps for the Spanish soldiers billeted in a hostile French village a long way from their homes, but in stark contrast to the violent events happening in the Chateau this same evening. Listen to it here.

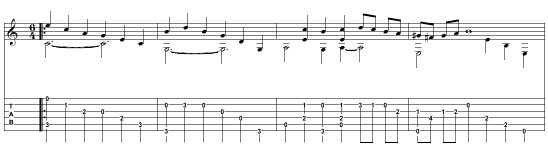

Score from www.free-scores.com

Enfin la Beauté que j’adore (‘At last, the beauty that I adore’) is one of the great ‘airs de cour’ by 17th century composer Etienne Moulinie, and by far the most modern piece cited in the manuscript, the songs having only been published between 1624 and 1635. It is sung by Crespin de Chouy as he rides to the Hermitage in chapter 25, and reflects his far more up-to-date Parisian cultural background. Listen to it here.