![]()

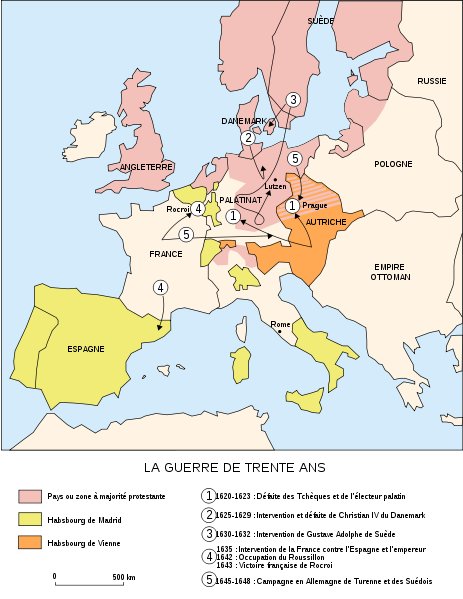

The Thirty Years War of 1618-1648 was fought between the great Catholic powers of Spain and the Holy Roman Empire on the one side, and the predominantly Protestant nations on the other. The different causes and phases of the conflict are far too complex to be dealt with here, but there are a great many excellent books on the subject, some of which are listed in the Bibliography. What follows is necessarily a very simplistic description, designed only to give background and context to the world of the Chevalier series.

The part of the War which most concerns us is the so-called French Phase, which began in 1635 when Cardinal Richelieu brought France into the war on the side of the Protestant Swedes and Dutch. It should not surprise us that a Catholic nation should fight against the forces of the Holy Roman Empire and the Catholic League, since by this time the original religious causes of the conflict had already become of secondary importance to the struggle for dominance in Europe. France was surrounded on three sides by Habsberg powers, and Richelieu feared an Imperial victory would be dangerous for France’s future.

He was quite right. Spain had an eye to the growing militarism of France, and was aware that a new power was rising to threaten her own previously unassailable position in Europe. In the mighty tercios Spain had what some would claim to be the finest army in the world, and she was in no mood to tolerate an upstart nation seeking to rival her achievements. Although the conflict continued to rage all over the Continent, the rivalry between Spain and France came increasingly to dominate the stage, so that even when the Thirty Years War ended officially with the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 the Franco-Spanish War continued for a further eleven years. It is perhaps fitting that the forces which overrun the Saillie in Honour and the Sword should be Spanish, although other Imperial armies also participated in the invasion, and it was a German force under the great Johann de Werth which actually penetrated closest to Paris.

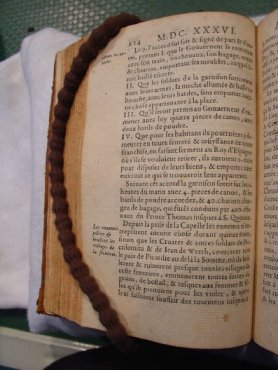

The brutality of the attack, including the slaughter and rape which takes place at Ancre, may seem to us extreme, but the Mercure Francois for 1636 speaks specifically of the savagery of the enemy troops and the atrocities committed against civilians, including women.

This is, of course, a biased account which naturally seeks to demonize the enemy, but the Spanish Army of Flanders did enjoy a particularly wild reputation even among its own people. In The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road, for instance, Geoffrey Parker quotes Francisco de Valdés’ remark that ‘the day a man picks up his pike to become a soldier is the day he ceases to be a Christian.’

Mercure Francoise; http://mercurefrancois.ehess.fr/

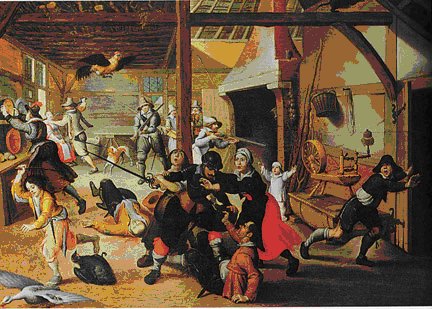

It was not, however, only the Spaniards who became soldiers, and the Thirty Years War is generally characterised by extreme barbarity practised on all sides, usually at the expense of the civilian population. Many paintings depicting pillage, rape and the firing of villages survive from this time.

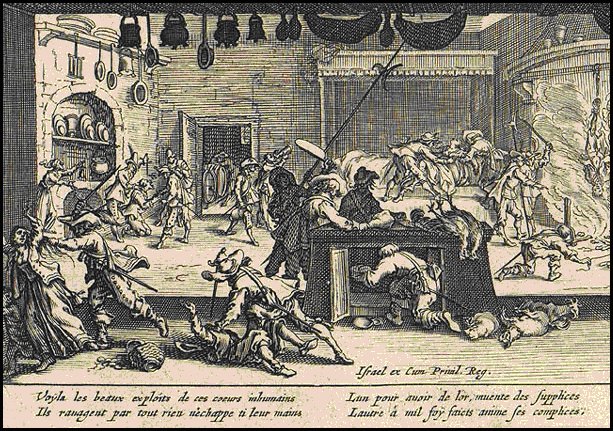

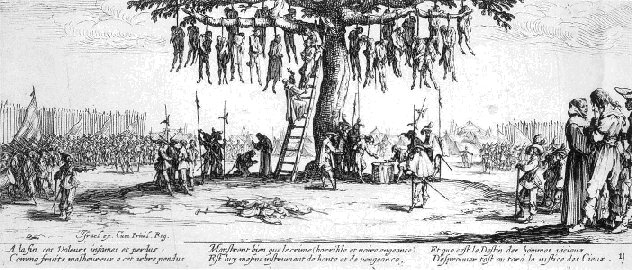

Jacques Callot’s two series of etchings depicting the Miseries of War illustrate particularly starkly the reality of life during the Thirty Years War.

Even apparent atrocities committed in Honour and the Sword were in reality commonplace, and we should not be misled by the French narrators into believing the Spaniards were worse than anybody else. Desecration of the dead, for instance, was widely practised in order to intimidate a local population or simply as part of the wildness of the initial rampage. At Eichstätt in 1633 even the bodies of nuns were dug up in the convent graveyard ‘leaving one deceased Sister with her right hand upraised’ (eyewitness account of Clara Steiger).

Nor was it generally as shocking to the population as it would be today. France herself routinely degraded the corpses of criminals as part of their punishment for their crime, and the only element of Don Francisco’s actions which can legitimately draw censure from our narrators is their own perception of the victims as innocent. The most famous picture from Les Misères de la Guerre shows the law can be quite as brutal as the criminal:

The Chevalier series deals not only with the sufferings of civilians, however, but also with the business of the War itself. In Honour and the Sword the focus is naturally on our charcters’ own small patch of Picardy, but In the Name of the King takes us out into the wider world of what this war truly meant. The destroyed and abandoned village of Petit-Grouche became for Jacques an emblem of how the Spanish invasion had devastated the country he loved, but such scenes could have been replicated all over the continent, where massacres were perpetrated by armies on both sides.

It is also in the manuscripts of In the Name of the King that we are given our first sight of the great battlefields, from La Marfée in 1641 to Rocroi in 1643. These are both unusual, being pitched battles on open fields rather than the more usual business of a siege, but each in its own way typifies much that is characteristic of the Thirty Years War. La Marfée, for instance, is fought between an extraordinary mix of combatants, with a combined force of the Holy Roman Empire, Rebel French, Sedanaise, and Spanish taking on the forces of France loyal to the King.

‘Battle of La Marfée’ by Stefano della Bella

This strange combining of nationalities can be seen also in the ‘off-stage’ Battle of Honnecourt, while the reserves with whom our characters are forced to hide contain Germans and Italians as well as Spanish and Walloons.

Rocroi is traditional in a different way, representing one of the last great battles of the Spanish tercios. The battle technique is classic in its structure, both in the arrangement of the opposing lines and in the business of attack and counter-attack, showing not only the true role of cavalry but also the increasing importance of guns and heavy ordinance.

Battle lines at Rocroi

More details of the weaponry and techniques employed at this time can be found in the Warfare section.