![]()

Northern France has seen more of its share of war, and a reader retracing André’s footsteps in In the Name of the King will find many of the place names evocative of a later, tragic conflict. Artois, Picardy and Champagne all suffered dreadfully in the Great War of 1914-1918, and a visitor today to the little village of Épehy on the Picardy/Artois border will be greeted by a sight all too familiar to this region:

Epehy Wood Farm

Even the nearby Malasisse Farm where our band of characters take refuge before the incursion into Artois is a name better known today for a famous battle fought there in March 1918. There is a farm on the site to this day, but it has had to be reconstructed around the remnants of the original buildings of 1632.

Malasisse Farm © Chris Baker, The Long, Long Trail

The land itself is unchanged, and we can still see the road by which our characters would have crossed the border, and the copse which is all that remains of the wood where the ambush was sprung:

|

|

| Road north from Malasisse, © Chris Baker, The Long, Long Trail | Copse seen from the north, © Chris Baker, The Long, Long Trail |

I am indebted for these pictures to Chris Baker, whose site The Long, Long Trail: The British Army in the Great Warbears witness to many years of dedicated study, and is well worth a visit to anyone interested in this period.

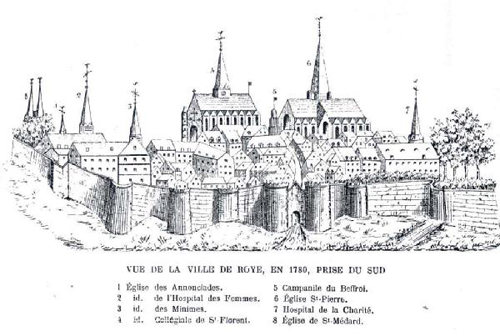

The towns, however, are a different matter, and many of those through which André passed have been rendered unrecognizable by the destruction of the 20th century. Roye, for example, in the Somme valley, can only be reconstructed for the historian with the help of old town plans, like this one from 1780:

In many respects we would regard such towns as mediaeval, although there were sound practical reasons for their design. The town walls (common to any settlement of size in this period) were essential in a time of civil strife as well as major wars, while the allocation of trades to specific areas referred to in Grimauld’s mention of ‘the livestock quarter’ was a matter not just of social status but of hygiene.

Bernadette’s reference to the Hôtel de Ville identifies the market square where André unexpectedly encountered a face from the past, which must have been this space here:

Hôtel de Ville, Roye

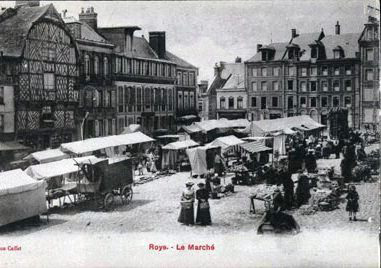

The roads, however, have been widened considerably since the 17th century, and the original market which blocked our characters’ route would have looked rather more like the pre-war image in this old postcard:

Old market, Roye

But Roye is not the only town our characters explore. Lucheux we have already studied as the nearest town to Dax itself, but the documents of In the Name of the King give us a little more detail. The unfortunate incident that takes place there occurs by the exterior of the St-Léger church, which still stands to this day:

St-Léger Church, Lucheux

| The interior has changed little, and Jacques’ comment about the ‘statues and paintings of him with his head off’ is as true today as it would have been in 1643: |  |

| Statue of St Léger, Lucheux |

Senlis too is mentioned, where Jacques stopped to change horses, and here we can still find remnants of the older time:

|

|

| 18th century map, Senlis | Senlis |

Senlis was a major city in the 17th century, but unfortunately Jacques saw little of it beyond the courtyard at an inn, and only the fact that he rode through ‘the gates’ tells us that Senlis too was walled.

The most important town to our characters was undoubtedly Rocroi itself, outside which was fought one of the greatest battles of the century. The town is miraculously untouched, and we can still see the remnants of the original fortifications.

Fortifications at Rocroi

These are star-shaped, and were designed that way even before the great Vauban developed them later in the century:

17th century engraving of Rocroi

Most of the houses are from the 18th and 19th centuries, and it is the more extraordinary to see them cheek by jowl with earthworks and walls from the time of the Thirty Years War.

Fortifications on the edge of Rocroi

There is also a charming little museum here, the Musée de le Bataille de Rocroi, which is staffed by local inhabitants. They do not themselves speak English (nor should it be expected) but they are wonderfully friendly and knowledgeable, and the splendid interactive display has an audio commentary in English.

Museum of the Battle of Rocroi

Students of the Battle of La Marfée will fare less well, as there was no town involved and there is little to see now but the field of battle itself. Even that, however, is of interest, as the visitor will see at once the strategic importance of the high ground which Châtillon’s army so desperately hoped to achieve:

Battlefield of La Marfee

The forest has shrunk a little since 1641, but there is still enough to see the woods in which the fugitives took refuge. This photograph, taken again from the Heights, shows the field below the battle where the baggage train would have been, and we can see quite clearly the tree-line into which so many of our characters were forced to flee.

From La Marfee looking out to the Sedan

But there is more to France than towns and battlefields. A significant portion of the documents comprising In the Name of the King concerns André’s time in the vicinity of Compiègne, and this is one of the most fruitful areas for any lover of history to explore. The Forest itself is magnificent, and André was indeed fortunate to be wandering it in spring. Something of its size and density can be seen even in this modern photograph from the board of Compiègne Tourism, and it remains truly a place in which a man might hide undetected for many months:

Forest of Compiègne

But within it are hidden treasures, and one of the best is the village of Saint-Jean Aux Bois, of which Grimauld spoke so disparagingly – ‘It was built round the old Abbey, see, proper-walled and fortified with gates, but nothing worth the nicking inside, nothing but a church, a bakery, a smithy, and one little inn for the comfort of the lucky buggers that were passing straight through. Even the monks had scarpered for the city, and I couldn’t blame them.’

He was right about the monks, and the monastery had long been abandoned by 1640, but the village itself is precious to anyone who appreciates the lost world of our rural past. There are many more houses there now and I fear the tourist trade has already found it, but even that fact merely ensures it is all the more beautifully kept.

Saint-Jean aux Bois today

There are also sufficient remnants of the old time to keep a historian happy, such as these archways remaining from the time of the ancient walls:

|

|

| Old entrance to the monastery | Remnant of the original gate |

This is the world in which André de Roland lived. Horses once galloped through these openings, none perhaps with so urgent an errand as Jacques’, and one has only to stand under these stone archways to hear once again the clatter of desperate hooves.